On Art & Language

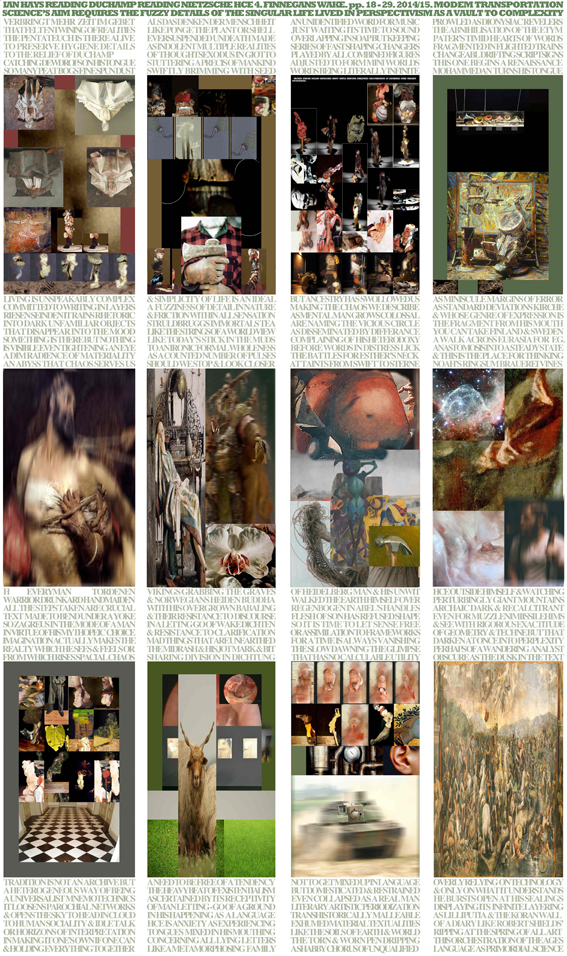

HCE can be thought as a mental machine whose genesis is: “in the hundred of manhood or proclaim him offsprout of vikings…”(FW.p.30 8-9). As transformation from Joyce and Duchamp naturally occurs as the processing of the “everyday” and further impossibilities under our eye the work becomes even more taxing – the doors to the Wake and Glass are of course still ajar.

On Art & Language

Finnegans Wake is a dense textured pattern of multi-referential words whose aim is to produce an unsystematic and loose corollary of allusions for the world of the mind. Here form is style, and the manner of the creative act is felt by the reader to be self-active and proactive – it is as though the natural spaces that occur between the text’s glyphs and the play of the grasping mind create elasticated threads of allusion whose characteristics are indeterminate as a consequence of this play where strands of mental exercise leap across ages and spaces of barely verifiable phenomena. This much we can easily observe without much fear of any argument as the world entire is given an imaginative shape inside the play of textual autonomy and hints, that in the word “tip”, for example, aids us in elevating the abbreviating lettering machine and its pattern throughout.

Joyce’s choices of placing further and further thoughts and concerns into each word creating enormous complexity for others to reassemble as they will, assays the contemporary world of language readers everywhere:

Far more people read Joyce than are aware of it. Such was the impact of his literary revolution that few later novelists of importance in any of the world’s languages have escaped its aftershock, even when they attempt to avoid Joycean paradigms and procedures. We are indirectly reading Joyce, therefore, in many of our engagements with the past half-century’s serious fiction – and the same is true of some not-so-serious fiction, too. Even those who read very few novels encounter the effects of Joyce’s revolution every week, if not every day, in television and video, film, popular music, and advertising, all of which are marked as modern genres by the use of Joycean techniques of parody and pastiche, self-referentiality, fragmentation of word and image, open-ended narrative, and multiple point of view. And the unprecedented explicitness with which Joyce introduced the trivial details of ordinary life into the realm of art opened up a rich new territory for writers, painters, and filmmakers, while at the same time it revealed the fruitful contradictions at the heart of the realist enterprise itself. (1)

A new visual art must be able to write about itself in our current time and space endlessly modifiable by the World Wide Web as an exhibiting site. Where else can image and text provide enlightened work within language from literature, art criticism, philosophy and poetics worldwide, and at greater speed, better than here? Our future, however, demands far greater understanding of what language is at its point of arrival to which we owe our existence, not merely the medium through which we travel every day everywhere blind and deaf to its application, and for every circumstance and desire, but from our amazement, astonishment, of language as entity.

Finnegans Wake actually provides us all with perspectives that awaken us to the differences that operate within ordinary language-use – casting itself against our so-called ‘ordinary everyday language’ that it parodies. How multifaceted language became and endlessly, seamlessly becomes in its ever-changing forms might be likened to the DNA/RNA template whose ‘instructions’ have coordinated and codify evolution. Language is the secret every human knows, it accounts for the world entire in the form of this open secret. Certainly Joyce wrote his book in part in order to put himself above ordinary languages – attempting to gain perspectival access to invisible chasms and secluded fragments of human historical detritus opened up by the variegated lights and limitless minds of his reader’s mental dictionaries. Jacques Derrida thought Joyce’s Wake displayed a vision or view of life as being infinitely more complex than trailblazing technologies and computerization, its self-styled text dominating the ruse of scientific exploration from a viewpoint close to Nietzsche’s thought on the inadequacies of science from the perspective of humanism and art. We are tasked with striving to comprehend a world of human experience by the resources of human minds – and technologies, however seemingly complex to us at present, are merely a tiny portion of that mind, however beneficial the results of technologies may prove to be or claim to become.

The commonplace or everyday is out of reach of the arts and writing: few texts on this suffice to show this more exactly than Blanchot’s Everyday Speech (2). The problem of denoting the everyday is just in this denoting. The arts find themselves at the extreme of non-everyday concerns even when they appeal to the ordinary and commonplace, drawing attention to the “subject”. The everyday is simply not a subject but rather background noise – the extra that has not been denoted and has not been noticed. The relationship between a complex book of the “everyday” like Ulysses and that of its readers who are the everyday is justifiably complex. Granted, the readymades of Duchamp showed an interest in selecting fairly ordinary day-to-day objects and furnishing them with the privileged title of works of art through display within a particular Western world culture: but the readymades, rather than being objects and items of the everyday, were selected for their amorphousness against other objects or tendencies particularly evident in the art of that time. They were not clichéd or commonplace as many commentators might have us think. Beyond this idea is the encounter with the “real” that for Duchamp at that space in time had become a rendezvous with the item in question that caught him partially unawares when daily seeking “a work that was not a work of art” but that would in time become one. An artistic hypothesis of this sophistication brings with it the full confidence of art history and theory that if continually debased during contemporary disinterest in the arts of the mind and its poetic will of course retreat beyond our horizons without our ever having known it. Something of vast intellectual prowess, the art of the mind, and the work of the imagination, appear already to be dead. Is it illiteracy in our generation that has condoned this condition? Or what do we mean by illiteracy? Illiteracy develops through the lack of reading beyond the school and the university, perhaps? Reading considered an obstacle that can’t be met on the plain of poetry and the philosophy of art.

Illiteracy has never been a problem for societies, however, and this appears natural until we think the significant possibilities of “culture” and “value” – terms that perhaps in our own epoch have become redundant. Duchamp’s point that after his own demise: “…art will go underground” is striking if only to underline the fact that intellectual study through art has indeed become, at the very least, invisible –

Most people of course have no interest in the commonplace or everyday and tend instead rather to emphasize its opposite that is the unusual, the different, the engaging.

If a diagram were made of consensual lives that played by its rules the pattern would be very interesting when measured against that of a person who was interested in the everyday because they are interested in art and ideas. But such a diagram would firstly need to be created starkly from the beginning to expose the differences clearly and in order to say something useful and unmistakeable from the outset.

(1) The Cambridge Companion to James Joyce. Derek Attridge (Ed.)1990.

(2) Maurice Blanchot. The Infinite Conversation. University of Minnesota Press. 2013.